Why Longevity Fails in Practice

Too Many Choices, Too Little Consistency

Longevity science has advanced dramatically over the past two decades. We now have a clearer understanding of the biology of aging, the behaviors that protect healthspan, and the risks that most strongly predict disease and decline. On paper, the path forward has never been more defined.

And yet, in practice, most people struggle to make lasting progress.

This is not because the science is inaccessible or unclear. It is because translating that science into consistent action over long periods of time is far more difficult than it appears. The core failure mode of longevity is not knowledge, but execution.

“People fail to consistently execute a small set of high-leverage behaviors over decades, even when they broadly understand what those behaviors are.”

Longevity Has Become Fragmented and Overwhelming

Part of the problem lies in how longevity is presented today. What was once a relatively small set of foundational principles has fractured into dozens of overlapping categories, each with its own language, tools, and priorities. Exercise protocols, nutrition frameworks, sleep optimization, stress management, metabolic health, cardiovascular fitness, cognitive performance, supplements, biomarkers, and biohacks all compete for attention.

Individually, many of these areas are legitimate and evidence-based. Taken together, they create cognitive overload. For most people, the challenge is no longer identifying what matters in theory, but deciding what to prioritize, what to ignore, and how to stay focused long enough for benefits to compound.

When everything feels important, consistency becomes the first casualty.

The Fundamentals Are Well Known, but Hard to Sustain

Across epidemiology, aging biology, and studies of long-lived populations, the same fundamentals appear again and again. Regular movement, preserved muscle mass, cardiovascular fitness, metabolic health, adequate sleep, stress regulation, and social connection account for a large share of long-term health outcomes.

These behaviors are not mysterious or novel. They work because they are high-leverage and cumulative. Their effects emerge slowly and compound over years rather than weeks.

That is also why they are difficult to sustain. Life becomes busy. Progress is hard to measure in the short term. Motivation fluctuates. Without structure, even disciplined people drift, experiment, and eventually abandon routines that once felt manageable.

Consistency over decades, not bursts of optimization, is where most longevity approaches break down.

Why Modern Environments Work Against Longevity

It is also important to acknowledge that consistency is harder today than it was for previous generations.

Modern environments are not designed to support long-term health. Many people spend most of the day sitting, working under constant cognitive load, and interacting more with screens than with their physical surroundings. Chronic stress, burnout, sleep disruption, and social disconnection are no longer exceptions. They are default conditions.

At the same time, exposure to ultra-processed foods and low-grade environmental stressors has increased, often without obvious short-term feedback. These forces rarely cause immediate failure, but they quietly erode metabolic health, resilience, and recovery over time.

The result is a constant headwind. Even highly motivated individuals are trying to build longevity habits in environments that make those habits harder to sustain. This is not a failure of willpower. It is a mismatch between modern systems and long-term biological needs.

How the Supplement Space Adds to the Problem

In theory, supplements should support healthy behaviors by reinforcing foundational biology. In practice, the supplement category often amplifies fragmentation rather than reducing it.

Most supplements are marketed as standalone solutions: one product for energy, another for inflammation, another for aging, another for focus. Each comes with a compelling narrative, but rarely with guidance on how it fits into a broader biological or behavioral strategy.

For people without the time or inclination to deeply evaluate the science, decisions naturally default to convenience and persuasion. What sounds compelling in a given moment tends to win. This leads to constant switching, inconsistent use, and supplement stacks built around trends rather than intention.

The result is effort without coherence, and activity without a clear long-term direction.

Why One-Off Solutions Rarely Change Long-Term Trajectory

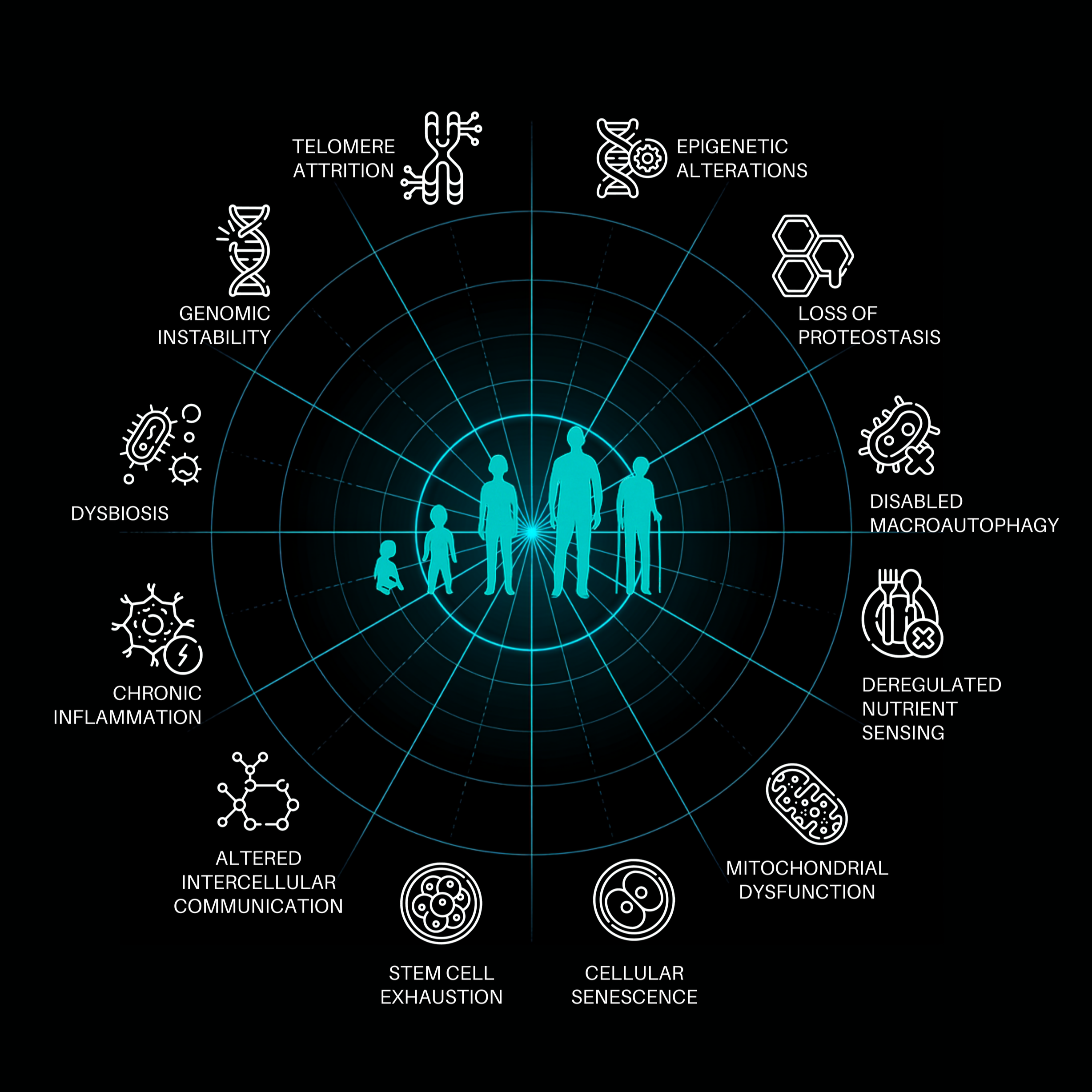

As the 12 Hallmarks of Aging illustrate, aging is not driven by a single pathway. It is a coordinated breakdown across multiple systems, including energy production, repair mechanisms, inflammation, communication, and regeneration.

Targeting one mechanism in isolation may produce a noticeable short-term effect, but it rarely alters long-term trajectory. Without structure, behaviors and interventions compete rather than reinforce one another. New additions crowd out old habits. Adherence fades, not because people lack discipline, but because the overall approach becomes unsustainable.

Most people are not failing because they are doing nothing. They are failing because they are doing too many disconnected things without a unifying strategy.

Why Systems Matter for Behavior, Not Just Biology

Systems thinking is often discussed in biological terms, but its real power in longevity is behavioral.

A system does not replace good habits. It reduces friction around them. By clarifying priorities, sequencing actions, and removing unnecessary choice, systems make consistency easier. Instead of constantly reacting to new information, people can rely on a stable structure that supports repeatable behavior over time.

This is how high-leverage actions compound rather than erode.

The Takeaway

Longevity is not about doing everything that might help. It is about identifying the few actions that matter most and creating conditions where they can be sustained for a very long time.

People do not fail at longevity because they lack information. They fail because consistency is difficult in a fragmented, high-noise environment. Solving longevity requires fewer decisions, clearer priorities, and systems that support long-term execution rather than short-term optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do most longevity approaches fail?

Most longevity approaches fail because people struggle to maintain consistent habits over long periods, especially when advice is fragmented and overwhelming.

What are high-leverage longevity behaviors?

High-leverage behaviors include regular movement, cardiovascular fitness, metabolic health, quality sleep, stress regulation, and social connection. These behaviors compound over decades.

Why is consistency more important than optimization?

Small actions repeated consistently over many years have a greater impact on healthspan than short-term optimization efforts that are difficult to sustain.

Why are supplements often disappointing for longevity?

Supplements are often taken in isolation without a broader strategy. Without structure and consistency, one-off supplements rarely change long-term health outcomes.

How does the modern environment affect longevity?

Modern environments often discourage movement, disrupt sleep, increase stress, and promote sedentary behavior, making long-term health habits harder to sustain.

How does systems thinking help with longevity?

Systems thinking reduces decision fatigue and clarifies priorities, making it easier to repeat high-leverage behaviors consistently over time.